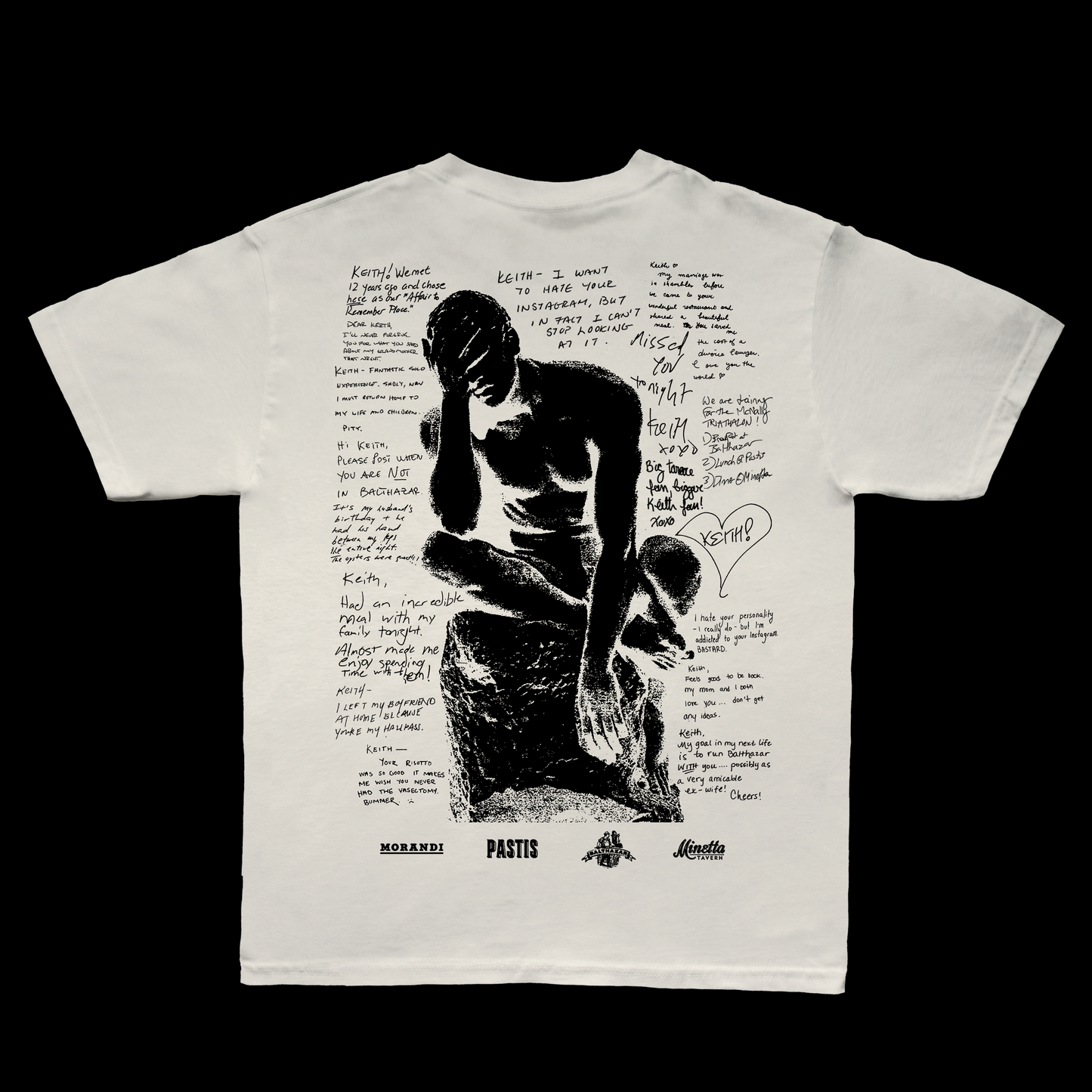

Dead Beat Tee (SOLD OUT)

Dead Beat Tee (SOLD OUT)

Couldn't load pickup availability

ORDER OPEN: 7/24/25

ORDERS CLOSE: 7/28/25

TO PRINT: 7/29/25

PRINTED ON CREAM LOS ANGELES APPAREL TEES.

UNISEX. MADE IN U.S.A. 100% COTTON.

ALL ITEMS TAKE BETWEEN 3-5 WEEKS TO PRODUCE AFTER THE ORDER PERIOD ENDS. You will always receive your item unless otherwise contacted. All items are final sale. We are not responsible for lost, stolen, or misplaced packages.

Since 1980, McNally has opened a series of stylish, bustling Manhattan restaurants—the Odeon, Balthazar, Schiller’s Liquor Bar—that helped to define their moments. Several have grown into New York institutions. Almost all have offered a combination of painstaking aesthetic nostalgia, classic bistro food, and nonchalant service—a well-honed formula heavy on steak frites and subway tile. Perhaps the apex of McNally’s success has been Balthazar, a SoHo brasserie in a cavernous space that once contained a leather warehouse. The inspiration for the restaurant was a century-old photograph he’d found at a Paris flea market showing a zinc bar flanked by caryatids, in front of a wall of liquor bottles twenty feet high. From this sepia-toned image sprang Balthazar’s clattering dining room, which opened in 1997 to celebrity crowds, then matured into a local fixture and even a bit of an empire, with an outpost in London and a wholesale bakery operation.

“In describing how Balthazar came about, I’d like to recall an early family holiday in the south of France where I experienced my first taste of foie gras,” McNally writes, in an introduction to the restaurant’s 2003 cookbook. “I’d like to, but it’d be a complete lie.” Born in London in 1951, McNally grew up in the East End neighborhood of Bethnal Green. His father was a stevedore and his mother an autodidact who aspired to something better than the prefab house where her family lived. Her son recalls it as a place of “cheap linoleum” with walls that “were made of a material so thin you could punch a hole through it.”

It’s not hard to see, in McNally’s restaurants, evidence of a thwarted Hollywood sensibility: the splashy guests they courted, but also the lavishly realized lighting and scenery. Over the years, his irritation with critics has often concerned their tendency to fixate on appearance and ambience—and to be, on occasion, less than effusive about the food. “Just as beautiful women have a hard time being taken seriously, so it is with restaurants,” he observes. Yet, in his view, neither food nor design is enough to guarantee a restaurant’s success. “Nothing does,” he writes, “except that strange indefinable: the right feel.”

It’s not hard to see, in McNally’s restaurants, evidence of a thwarted Hollywood sensibility: the splashy guests they courted, but also the lavishly realized lighting and scenery. Over the years, his irritation with critics has often concerned their tendency to fixate on appearance and ambience—and to be, on occasion, less than effusive about the food. “Just as beautiful women have a hard time being taken seriously, so it is with restaurants,” he observes. Yet, in his view, neither food nor design is enough to guarantee a restaurant’s success. “Nothing does,” he writes, “except that strange indefinable: the right feel.”

Fittingly, McNally’s ascent began with the crank of star-making machinery. After leaving school at sixteen, he was working as a bellhop at a London Hilton when an American film producer asked him to audition for a part. In due course, he was cast as an urchin in a movie about Charles Dickens, and soon a black Bentley was ferrying him to the set. McNally’s career as an actor was brief—a few years onstage and onscreen—but it was enough to sand off his working-class accent. It was also an introduction to a wider world: Alan Bennett became his friend and later his lover, and McNally used the money he earned from acting to travel. (Inspired by Hermann Hesse’s “Siddhartha,” he set out for Kathmandu, following the Zeitgeist across India.) After a period of backpacking abroad and menial labor in England, in 1975 he moved to New York, where he found work first as a busboy and then as an oyster shucker at a restaurant downtown called One Fifth. Staff turnover and personal charm allowed him to climb the ranks quickly. “Customers could be surprisingly forgiving once they heard my English accent,” he notes.

By 1977, New York magazine declared the twenty-six-year-old McNally “the youngest of the important maître d’s” in the city. At One Fifth, he began assembling the cast who would join him in his later endeavors. He hired Lynn Wagenknecht, an aspiring painter, as a waitress (they soon began dating), and his older brother Brian as a bartender. Anna Wintour was a pretty One Fifth regular for whom McNally once ducked behind a stove to cook eggs after the kitchen had closed. They became friends, and when she started dating a Frenchman she flew McNally and Wagenknecht to Paris to keep her company. There, McNally’s fascination with archetypal French brasseries and bistros took hold. “I loved the smell of escargots drenched in butter and garlic, the look of the red banquettes, the scored mirrors, the handwritten menu, the waiters with starched white, ankle-length aprons,” he writes evocatively of his favorite, Chez Georges. He began to entertain the possibility of running such a place himself. Aside from describing Wintour’s crucial intervention, he betrays little introspection about this turn. “Lynn and I decided to open our own restaurant,” —and so, along with Brian, they did.

To want to own a restaurant can be a strange and terrible affliction,” Bourdain writes in “Kitchen Confidential.” The economics are daunting, the odds of success bad. “What causes such a destructive urge in so many otherwise sensible people?” Bourdain asks. A desire for sex, he hypothesizes, and for life-of-the-party panache; would-be owners want “to swan about the dining room signing dinner checks like Rick in ‘Casablanca.’ ” In Bourdain’s assessment, restaurant ownership holds the illusory promise of easy pleasure—but it’s also the perfect venue to work through whatever baggage you’ve got about your family. After all, a restaurant is a place where you provide the sustenance, you decide who belongs, you make the rules.

Share